by Antonio Michele Storto

“We will wipe out Terroristan”: The long-awaited announcement has been circulating for weeks, and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has officially pledged to “permanently eliminate” the long-standing threat posed by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) guerrillas. The independence movement has been locked in conflict with Ankara since 1984, resulting in thousands of civilian and combatant deaths. Erdoğan’s firm commitment underlines the gravity and enduring complexity of the regional challenge.

In a statement released after the cabinet meeting on 4 March, Erdoğan announced a massive military operation to target PKK strongholds in northern Iraq and their YPG counterparts in northern Syria. According to Turkish newspaper T24, the offensive will begin immediately after local elections on 31 March. “If everything goes according to plan, by the summer we will have finally solved the problem of our Iraqi borders,” declared the Turkish President, who intends to repeat the project already underway in Syria by creating a 30-kilometre buffer zone in Iraq as well. “We are making preparations that will give new nightmares to those who think they can bring Turkey to its knees with a ‘Terroristan’ on its southern borders,” said Erdoğan.

But if the stumbling block in Syria is mainly diplomatic – since the People’s Defence Units (YPG) fighters are still Washington’s main local allies – the matter is much more complicated in northern Iraq, where the PKK’s presence dates back to 1981, in a decades-long affair whose evolution vividly illustrates the fractures and contradictions within the Kurdish ethnonationalist movement.

The area, a mountainous and inhospitable region technically under the jurisdiction of the Autonomous Region of Iraqi Kurdistan (KRG) since 1992, was for over a century a fiefdom of the Barzani clan, which has administered the KRG for four generations and represents the longest-lived and “noblest” of the historic dynasties in the Kurdish independence movement: It was the Barzanis who were responsible for some of the first Kurdish uprisings in the region in the early 20th century, around the time of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

Led by landowning families devoted to Sufi Islam and lamenting the gradual loss of autonomy within the empire while asserting secular demands, Kurdish nationalism at the time expressed demands that were very different from those of a socialist nature that would emerge with the Second World War.

In the late 1970s, Abdullah Öcalan, the founder and historical leader of the PKK, marked the movement’s definitive departure from its once “noble” roots. Born into a family of agricultural labourers in south-eastern Turkey, where the Kurdish independence movement appeared to have been crushed after the failure of the Dersim uprising in 1938, Öcalan constructed his ideology through a radical critique of leaders such as Mustafa Barzani. The PKK’s doctrine identified figures like Barzani, a hero of the Kurdish-Iraqi resistance, as the embodiment of a feudal mentality even more harmful than the repression of national governments.

In 1981, after succeeding his father Mustafa as head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), Masoud Barzani allowed the PKK to establish itself in the mountains of the Lolan Valley, near the Iranian and Turkish borders, which had been controlled by his clan for decades. At the time, it was a necessary compromise for the Barzanis, who risked being marginalised by the upheavals that the conflict with Tehran was bringing to the Kurdish-Iraqi world. Öcalan saw this opening as a crucial opportunity for the success of his insurgency, which was to begin three years later. For more than a decade, the impenetrability of these mountains and the porosity of the nearby Turkish border allowed the PKK to establish deadly lines of infiltration that stretched from the Iraqi bases into the Turkish hinterland through a network of paths and villages that had been travelled by generations of smugglers.

But the idyll with the Barzani clan was not to last. Turkey’s support for the establishment of the no-fly zone in 1992, which laid the foundations for the birth of the KRG, marked the first convergence of Turkish and Kurdish-Iraqi interests. In April of that year, the two leading parties in the newly formed Kurdish region signed an agreement with Ankara in which they pledged to cease all forms of support for the PKK and to counter its incursions into Turkish territory.

Starting in the summer, over three thousand troops – including Turkish special forces and Iraqi Kurdish peshmerga – backed by Ankara’s air force, launched an offensive against Öcalan’s fighters, killing and capturing almost a third of the troops stationed in the area.

But just as Ankara began to consider the “Kurdish problem” solved, a civil war broke out between the two Kurdish-Iraqi parties, giving the PKK another opportunity to reorganise. Military bases and installations were moved to Qandil, in the Zagros Mountains, at an altitude of 3,500 metres, in an even more confined and inaccessible area, practically straddling the Iranian border: from here, Öcalan began to gradually transfer the last remaining command and training centres from the Beqaa Valley in Lebanon.

Since the mid-1990s, the PKK has controlled an area of 50 square kilometres in Qandil, which has proved virtually impregnable thanks to a series of tunnels dug into the rock. In 2008, the Turkish Air Force began to carry out increasingly intense and frequent air strikes, which, according to reports from various humanitarian organisations, have mainly affected civilians in the surrounding villages.

Meanwhile, tensions between PKK guerrillas and Barzani’s KDP have also gradually increased as diplomatic and economic ties between Erbil and Ankara have strengthened. Since the end of 2016, skirmishes between the Iraqi Peshmerga and PKK militiamen – who have been repeatedly asked to leave the region – have become more frequent and violent, especially in the Dohuk area and earlier in the Sinjar Valley, where the presence of guerrillas has increased after the fight against Islamic State.

These tensions reached a peak in the spring of 2021 when the Kurdish regional government authorised Ankara to build a series of military outposts along the border between the two countries as part of “Operation Claw”.

“We have been and are trying to de-escalate the problems, but this time it seems to be out of control because Turkey has invaded a 100-kilometre-long and 35-40-kilometre-deep piece of land in its offensive in South Kurdistan. It has also deployed its troops there, set up military bases, cleared roads and brought all the military technology it has from NATO,” Mohammed Ameen Penjwini, a veteran politician who previously mediated between the KDP and the PKK, told Rudaw.

These troop deployments haven’t been without casualties. Erdoğan’s latest threats follow the deaths of 12 Turkish soldiers in a series of shootouts with guerrillas in the region in recent months. “We will wipe out this Terroristan,” the Turkish president shouted on 13 January, the day after nine soldiers were killed and four others wounded in a fierce shootout.

But the question is legitimate: Can the Turkish army achieve in four months what it has failed to do in the past three decades?

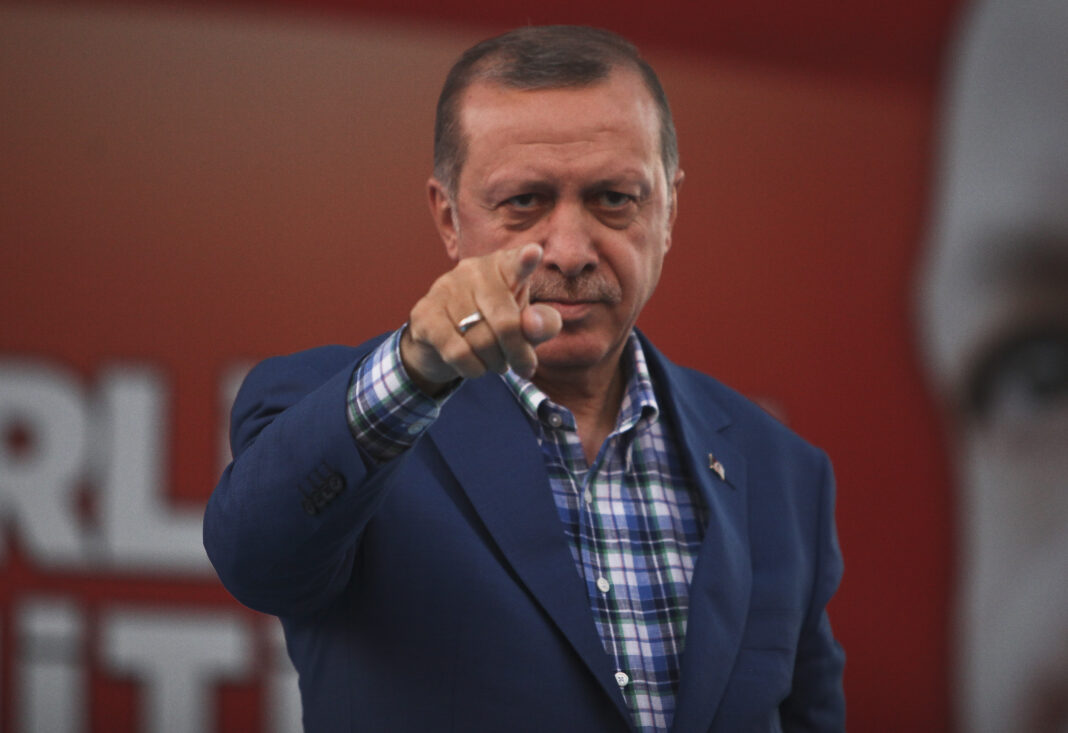

On the cover photo, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ©kafeinkolik/Shutterstock.com