By Aine Bennett

Reports emerged earlier this year of Ukrainian border guards preventing trans people, particularly trans women, including those with legal recognition of their gender, from exiting Ukraine following Russian bombardment. These episodes have cast a light on the specific security risks to LGBTQ+ people in situations of conflict and forced displacement, as well as the significant obstacles to international mobility and accessing international protection many LGBTQ+ people face.

The first Pride parade was held in June 1970 to mark the anniversary of the Stonewall riots, an uprising against police violence. Pride month therefore continues to provide a moment to reflect on ongoing state violence against queer people, both through criminalisation or persecution in LGBTQ+ people seeking asylum’s countries of origin and through the bordering regimes and barriers to asylum posed to LGBTQ+ people by refugee receiving states.

Legal Basis for Asylum

There is limited data available but the UNHCR found in 2021 that most industrialised and several middle-income states now recognise sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) as grounds for refugee status. The 1951 Refugee Convention defined a refugee as any person who:

“owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”

The convention entails certain obligations for contracting states, particularly that they must not return a refugee to a territory where their life or freedom would be threatened due to any of these grounds, which is known as the principle of non-refoulement. SOGI asylum is usually based on including LGBTQ+ people in the definition of “a particular social group”.

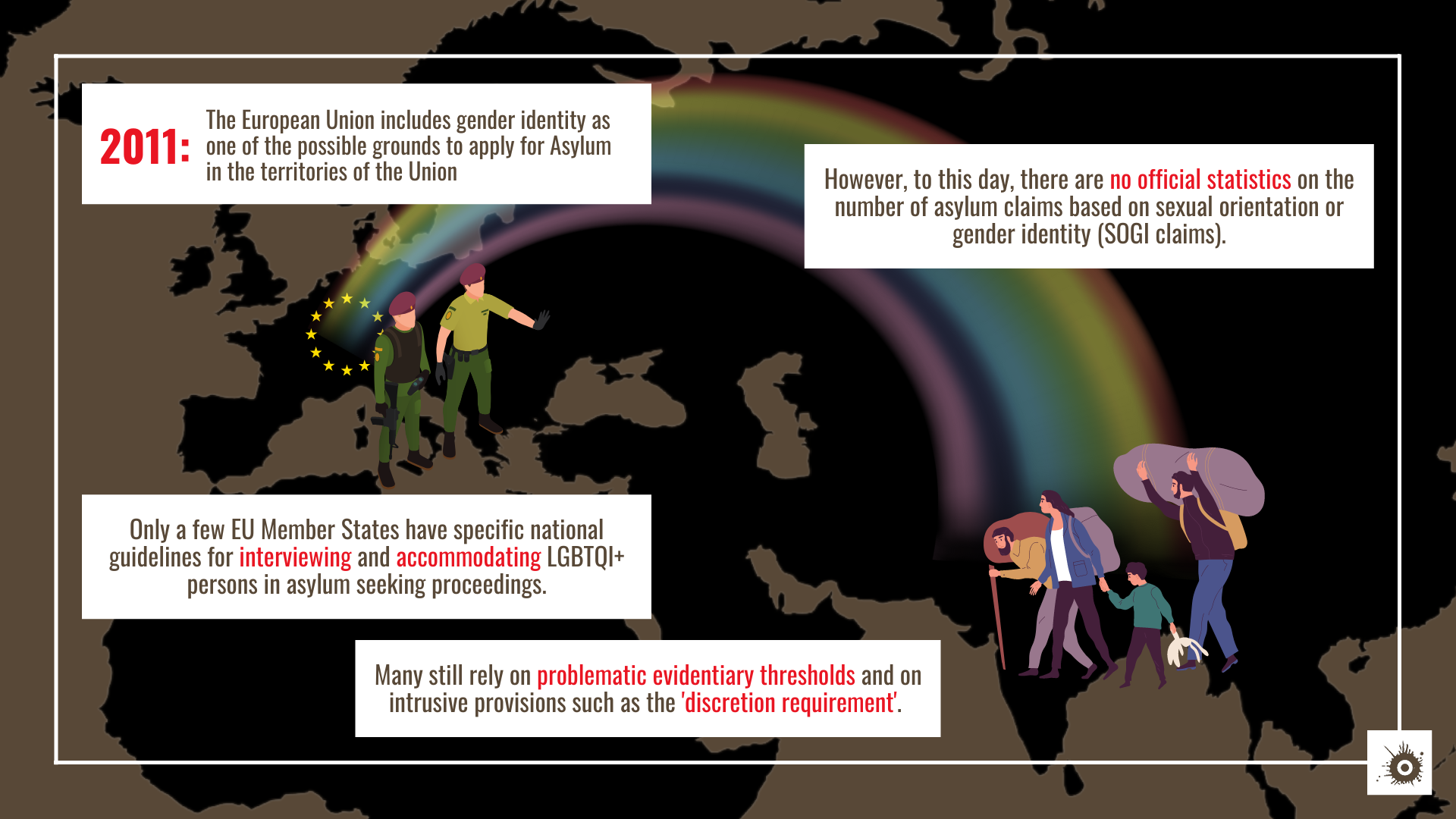

The first state to grant asylum on the basis of sexual orientation was the Netherlands in 1981, followed by several other states during the 1990s such as Canada in 1991, Australia in 1992, the USA in 1994, New Zealand in 1995 and the UK in 1998. In 2004, the EU delivered a Council Directive recognising the inclusion of sexual orientation in “particular social group,” which was expanded in 2011 to include gender identity. The UNHCR released its first legal interpretative guidance for assessing SOGI asylum claims in 2012.

Obstacles to Recognition: discretion and disbelief

While there are significant variations in the experiences and treatment of people seeking SOGI asylum between different states, there are some common obstacles to the recognition of claims that arise in many states.

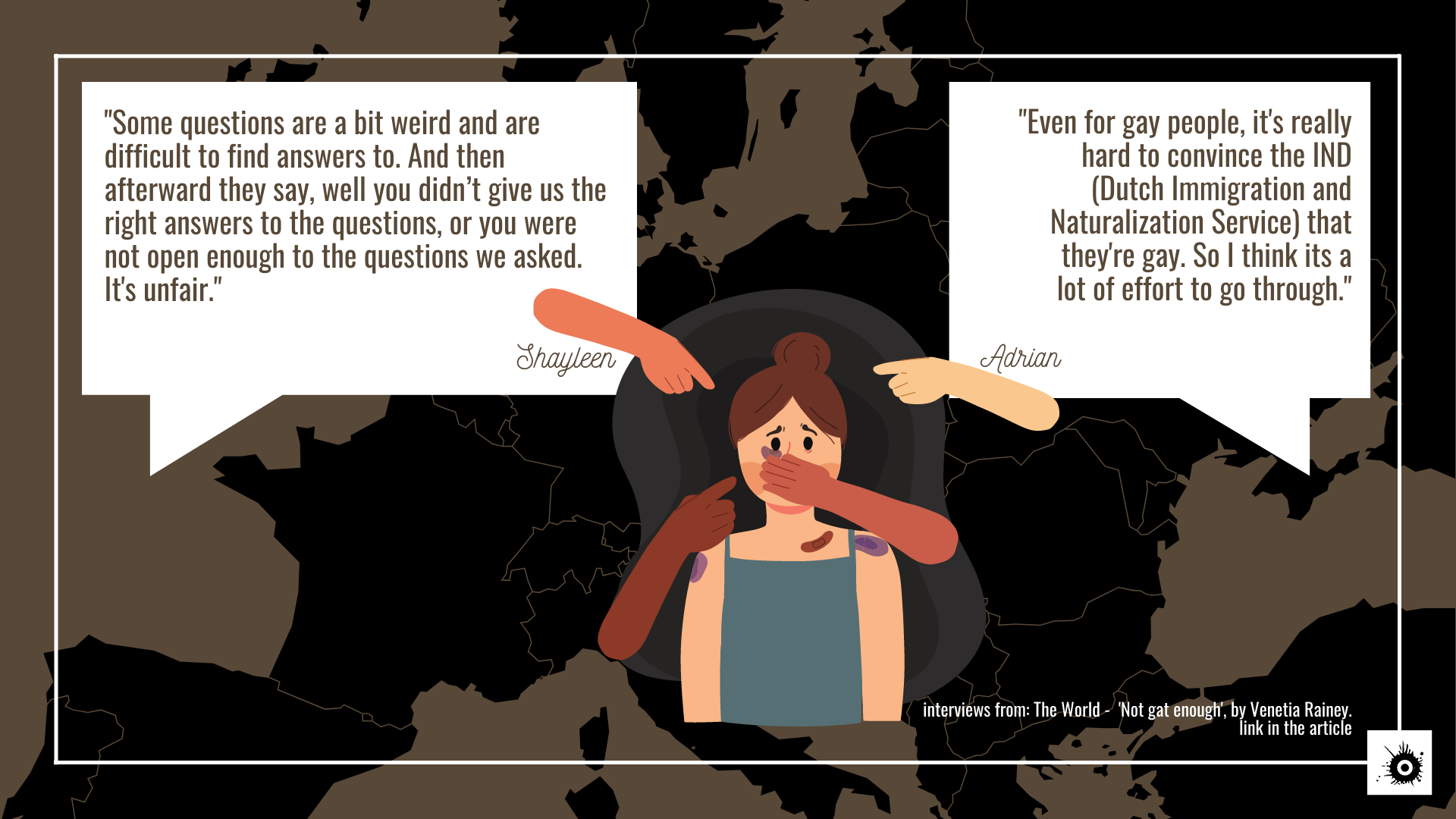

One of the common obstacles historically has been the ‘discretion requirement’ which denies claims due to the expectation that applicants can return and avoid persecution by being ‘discreet’ about their sexual orientation or gender identity. The Fleeing Homophobia report found as recently as 2013 that while the requirement had been abolished in a few European states, it was commonly applied in the “large majority of European states.” The SOGICA project found in 2020 that, despite the CJEU having deemed this reasoning unacceptable since 2013, some Member States still return claimants who they consider would be discreet by ‘choice’. This approach restricts access to refugee status for LGBTQ+ claimants; makes the claimant responsible for their own protection, rather than states; and ignores the fact that even a ‘discreet’ LGBTQ+ person’s sexuality could always be exposed, putting them at further risk of persecution or exploitation.

While the use of discretion reasoning appears to be declining, asylum decision makers in Europe commonly reject claims on the basis that they do not believe the applicant is gay. According to the SOGICA project, decision makers in EU states often start from a scepticism that claims are genuine. The impact of this can be seen in cases such as Shayleen’s, who was jailed without trial in Uganda for being a lesbian and fled to the Netherlands, where immigration authorities did not believe she was a lesbian and rejected her asylum claim.

Risks for LGBTQ+ people seeking asylum

While SOGI claimants flee persecution in their countries of origin, they are often still unsafe in reception countries. ILGA Europe, the UNHCR, and SOGICA have identified continuing risks to LGBTQ+ people and additional protection needs – risks that often go unchallenged. All three point to the threat of harassment and violence in reception centres and migrant detention, especially for trans people, and the consequent need for safe accommodation; the need for access to adequate healthcare, particularly for trans and intersex people; and the need for inclusive interpretations of family reunification. Stonewall reports the example of a trans woman in the UK repeatedly being placed in male detention centres and facing threats of violence, particularly due to the shared bedrooms and communal showers in detention. ILGA, the UNHCR and SOGICA raise concerns that LGBTQ+ claimants are likely to delay reporting that their SOGI is part of the basis of their claim and that this is not sufficiently accounted for by receiving states. ILGA and SOGICA also criticise the use of ‘safe country’ lists and fast-track procedures for SOGI claims.

Cover Image: Valentina Ochner, 2022 (all rights reserved).