Wheat production and its export is at the centre of global geopolitical issues, and has been even before the war in Ukraine. Recently, the invasion of Ukraine, the climate issue and various other strategic factors affect the prices and spread of the cereal which, after maize, is the most widespread in the world.

In recent years, the global production of common wheat, whether for human consumption, animal feed or industrial use, has been between 700 and 750Mt (million tonnes) and corresponds to about 35% of world cereal production. The production of common wheat is essentially destined for about 70% for human consumption and about 20% for animal feed. Unlike maize, the use of common wheat for use in the energy industry is still marginal.

*Cover Image by Darla Hueske on Unsplash

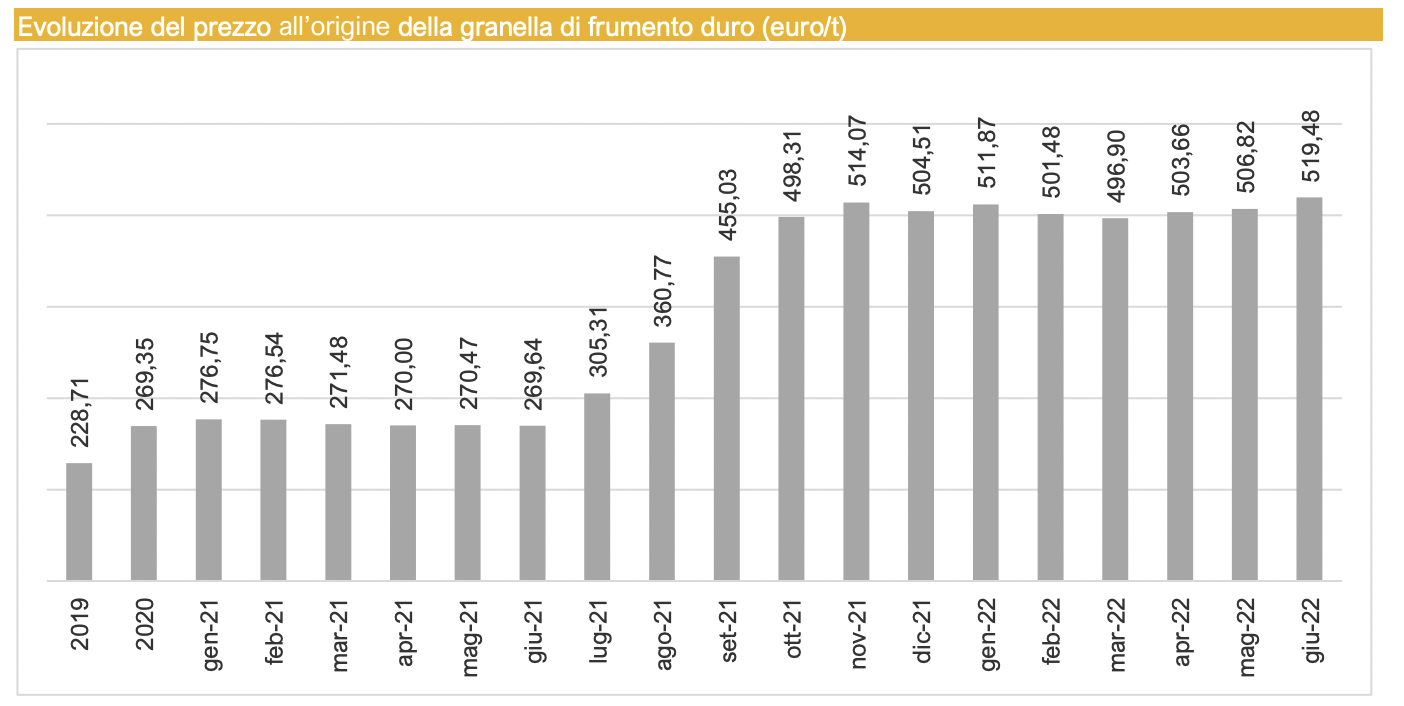

Graph below: the price growth of durum wheat (expressed in euros/ton), July 2022. Source: ISMEA (Institute of Agricultural Food Market Services, Italy).

The agreement on wheat circulation

To alleviate the food crisis caused by the war in Ukraine, an agreement was signed on 22 July 2022 after two months of negotiations. The agreement will last 120 days and concerns grain stored in silos in the Ukrainian ports of Odessa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny. The signatories from the two warring countries were Russian Defence Minister Sergey Shoygu and Ukrainian Infrastructure Minister Aleksandr Kubrakov. Monitoring the passage of the ships and compliance with the agreement from a coordination centre in Istanbul are representatives of Russia, Ukraine, Turkey and the United Nations. Among the conditions laid down for the agreement is the one wanted by Kiev, which prohibits sea demining. A condition placed in fear that Russia might take advantage of it to strike ports, Odessa in particular. Ukraine and Russia then gave each other guarantees that there would be no attacks on ships and military operations during loading and transport operations.

Less than 12 hours after the agreement was reached, however, Russian forces attacked the port of Odessa with cruise missiles and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Rudenko stated that the agreement could be terminated ‘if the obstacles to Russia’s agricultural exports are not promptly removed’.The routes from the ports of Odessa, Chernomorsk and Yuzhny will converge into a single route to Istanbul, where the ships will unload the foodstuffs. Here the ships will have to stop, unload and then turn back. The go-ahead will be given after an inspection to check that they are not carrying arms into Ukraine. As a result of the agreement, according to European Council President Charles Michel, 22 million tonnes of grain will be ‘freed’.

According to the UN and the World Food Programme, the conflict in Ukraine has triggered a food crisis that is pushing some 47 million people into ‘acute hunger’. Before the invasion, grain shipments from Ukraine amounted to around 5million tonnes per month. About 50 per cent of the grain blocked at Ukrainian ports is destined for World Food Programme projects in Africa.

Rising prices and adverse weather

The prices of energy and agricultural commodities are not only dependent on the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, but have been rising since the second half of 2020 due to a number of factors. On the one hand, the difficulty in the recovery of logistics to meet the intense recovery of global demand in the first post-pandemic phase, on the other hand, a significant increase in energy commodity prices in 2021 and the increase in demand for some agricultural commodities, with particular reference to the growing Chinese demand for cereals and soya.

An increase not justified, however, according to observers by global production and stocks of the main cereals, which were on the rise. The ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, however, was part of this context, putting further pressure on international markets, especially with regard to soft wheat, maize and barley. The war, however, has no direct relation to durum wheat, as world production and exports are in this case influenced by Canada, which, if it lost 60% of its harvests in 2021, is expected to reach standard production levels in 2022.

A major problem for harvests and the relative price of wheat are the extreme weather events that affect the whole world. Coldiretti estimates that world wheat production for the 2022/23 crop year will drop by 769 million tonnes. All this while world demand for durum wheat is expected to grow to 33.6million tonnes.

Droughts, floods, and heat waves threaten production in the US, Canada, France, India, and China, exacerbating the contraction of production in Ukraine. Almost all major producing regions faced a weather threat this harvest. The only notable exception is the Black Sea area, Ukraine and Russia in primis. Ukraine was indeed preparing for a bumper harvest but the war has reduced production and there are concerns about where to store the crop as the export backlog leaves silos full of last year’s wheat. Russia has also seen favourable weather and could instead reap a near-record harvest.

WHO DOES WHAT: maxi-imports, maxi-exports

According to the 2021 harvest data, China, with about 137 million tonnes (Mt) is the world’s largest wheat producer. In second place are India (110 Mt), Russia (75 Mt), the United States (46 Mt) and France (38 Mt).

The main exporters are Russia (34 Mt), the United States (24 Mt), Australia (23 Mt), Ukraine (23 Mt) and Canada (17 Mt). The European Union exports a total of about 33 Mt of soft wheat. The top importers in 2021 were Turkey, the Philippines, Japan, Indonesia, the European Union, Egypt, China, Brazil, Bangladesh and Algeria.

FOCUS 1: India stops its exports

To protect the domestic market from the global wheat crisis, India restricted the export of all types of wheat-derived flours on 12 July 2022. The Delhi government’s Directorate General of Foreign Trade (DGFT) has made it known that exporters will have to obtain special authorisation from the government to maintain quality and stabilise prices in the domestic market. “Disruptions,” the Dgft statement read, “in global supplies of wheat and flour have led to fluctuating costs and potential problems on quality.

But this is not the first time India has taken this decision as it had already banned exports last May. A decision that, coupled with the halting of exports from Russia and Ukraine, had contributed to the global increase and sparked heated criticism of Delhi. India is the world’s second largest wheat producer after China, but exports only 2% of its production and uses 80% for domestic consumption and storage. Due to the drought and the great heat in March and April 2022, there was a 5% drop in the harvested quantities.

FOCUS 2: The International North-South Transport Corridor

A passage destined to become increasingly strategic for the transport of grain and more is the International North-South Transport Corridor (Instc). This is a multimodal transport corridor established in 2000 that crosses the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea through Iran and is connected to St. Petersburg and Northern Europe via Russia. In 2005, Azerbaijan joined the project, followed by Belarus, Bulgaria, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Oman, Tajikistan, Turkey and Ukraine. This infrastructure allows Russia to reduce the travel time of goods between the Federation and India from 40 to 25 days because it allows them to bypass the Suez Canal.

With the ongoing food crisis due to the war, this corridor could, according to observers, allow Russia to unload its grain through Iran. In this way, Iran could become an important trade crossroads between Russia and India. For Dehli, too, this corridor represents an opportunity to extend its influence in Iran and Afghanistan and the rest of Central Asia, bypassing Pakistan.

Compared to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (the new Silk Road), the Insct is still in its initial stages of operation, but offers an interesting geostrategic contrast. By 2030, freight traffic between the countries involved and the South Asian and Persian Gulf area could amount to 245,000-501,000 TEU (4.4-9.0 million tonnes), or about 75 per cent of the potential total containerised traffic. Its expansion depends on how the transport infrastructure is improved and how far the digitisation of the international corridor has been achieved.