by Ambra Visentin

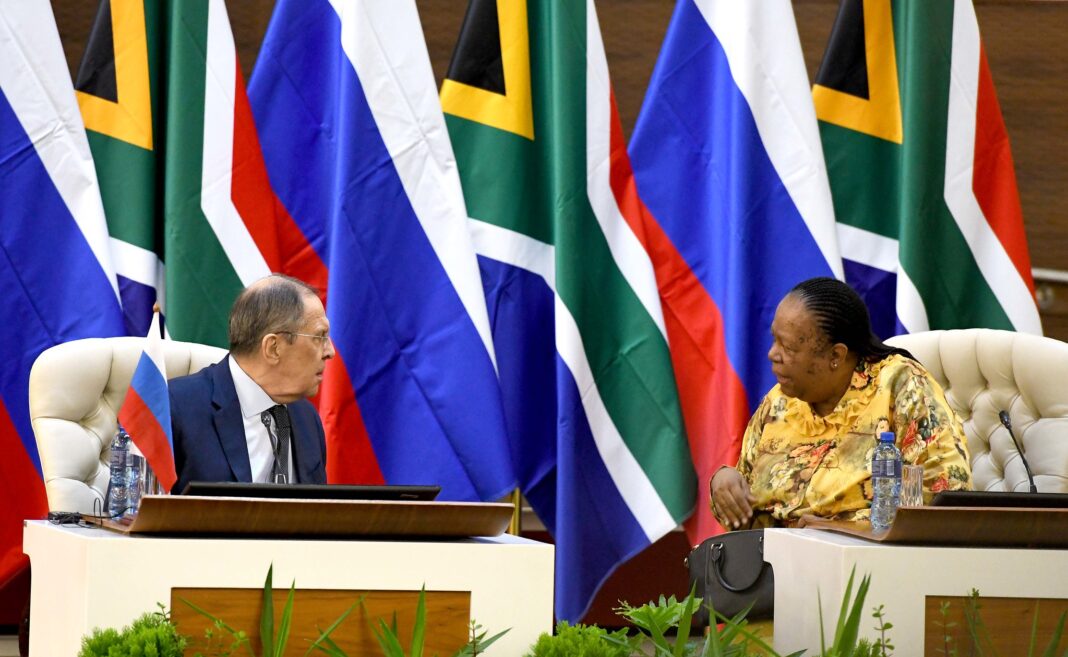

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov travelled to South Africa on Monday for talks with one of his country’s most important allies on an African continent divided by the invasion of Ukraine and Western attempts to isolate Moscow. In Pretoria, Lavrov met with his South African counterpart, Naledi Pandor. The two ministers pledged mutual support. Pandor spoke of ‘fruitful talks’, while Lavrov stressed the ‘regular political dialogue’ with South Africa and ‘extensive cooperation’ in the economic, high-tech and military fields.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s government considers South Africa to be neutral in the Ukrainian conflict and has expressed a desire to play a mediating role. “As South Africa, we reiterate that we will always be ready to support the peaceful resolution of conflicts on the African continent and around the world,” Pandor said in his speech alongside Lavrov. So far, South Africa has abstained in all UN votes on the war in Ukraine. This approach has not been without controversy at home. Opposition parties and the main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance (DA), have repeatedly called on the government to condemn the invasion and human rights abuses and to insist on Russia’s withdrawal, especially as the West is a far more important economic partner.

Pretoria shares with China and Russia a vision of a world without US hegemony, preferring instead a ‘multipolar’ world in which geopolitical power is more balanced. South Africa has little trade with Russia, and the second Russia-Africa summit will be held this year in order to intensify it. The close ties that existed between the African National Congress, now in power, and the Soviet Union during the struggle against the apartheid regime can still be felt today.

Russia’s return to Africa actually dates back to Vladimir Putin’s second term in office (2004-2008). Initially, it was part of a logic of ‘economic diplomacy’ and concerned countries (Algeria, Libya, Angola, Namibia, Guinea, etc.) in which the Soviet Union had invested considerable resources between the late 1950s and perestroika. Moscow is trying, with varying degrees of success, to mobilise its ‘Cold War’ networks and convert old ideological affinities into trade flows. Second, depending on opportunities and events, Russia is seeking to expand the geography of its interests to include states (notably Morocco, Nigeria, South Africa) that are historically anchored in the Western sphere of influence, have strong economic potential and can act as political relays in the sub-regions of the continent concerned or even beyond. Finally, since 2014 and the crisis in relations between Moscow and the West, the security dimension of Russian policy in Africa has been visibly strengthened, with some new aspects (the use of private military companies, the establishment of cooperation between local intelligence services and Russian ‘force structures’) being clearly more offensive.

There are other important ‘events’ on the 2023 calendar involving the two countries. South Africa is chairing the BRICS group of countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and will host a summit this year. The intention to cooperate militarily also emerged when the South African Department of Defence announced a joint naval exercise with Russia and China to be held from 17 to 27 February off the country’s east coast between Durban and Richard’s Bay. The exercise will take place on 24 February, the first anniversary of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Critics have described it as a questionable exercise at an inopportune time that could strain relations with the US and European countries. Instead, the South African government had previously described the brief one-day visit by the Russian foreign minister as ‘normal’.

Cover image: Sergei Lavrov and Naledi Pandor, © Dirco ZA on Flickr