By Theo Guzman

This reportage from Yangon appeared first on February 1st. It has since been updated as of February 2nd.

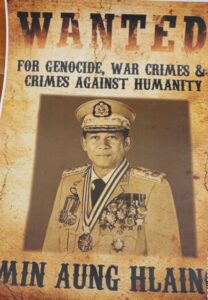

Returning from Yangon – On february 1st, 2023, yet another silent strike across most of Myanmar marked the the second anniversary of the military coup of 1 February 2021: a coup that outlawed Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy and imprisoned its leadership and thousands of activists and activists. The streets of Yangon, Mandalay, Naypyitaw, Monywa and other cities – reports a account by the Burmese online newspaper Irrawaddy – remained empty all day while residents stayed indoors although there were also small demonstrations and flash mobs in Yangon. Pro-regime demonstrations, on the other hand, took place in Yangon and Mandalay. The state of emergency has been extended for a further six months from the start of February: the regime media reported that the National Defence and Security Council granted Commander Min Aung Hlaing’s request to extend the state of emergency declared when the army overthrew the democratically elected government two years ago. Goodbye elections. It is a country under a slap in the face that we have just visited, but in which the strength of passive resistance is only partly grasped.

Unarmed resistance and civil disobedience in Myanmar also has the colour of beer: a drink which nobody drinks any more. Which is neither sold nor bought in the whole country, except in a few shops or restaurants that still serve and display Myanmar Bier. Burma’s most popular beer, already known to be a product of the economy of the same military that outlawed Aung San Suu Kyi’s party in a coup two years ago, is now the symbol of the silent resilience of millions of Burmese people. The boycott campaign, which began shortly after the coup in 2021 and is now two years old, is a reality we have touched upon in all the restaurants, cafes, street vendors, shops and shops. Here, the products of all those companies more or less directly linked to the military – the real masters of the local economy – are completely boycotted. It is a telltale sign that the war being waged, the one that crosses the entire country with the exclusion of the capital or the centres along the Irrawaddy river, is fought silently but sternly, even where no shots are fired. Take Yangon, for example. There, the apparent calm is punctuated by daily attacks. “The resistance doesn’t have the strength to take the city, but every day it makes itself heard,” confides a European diplomat. “You don’t see any military around? Of course, they are targets. They only go out in groups otherwise they risk it. They are afraid.”

Unarmed resistance and civil disobedience in Myanmar also has the colour of beer: a drink which nobody drinks any more. Which is neither sold nor bought in the whole country, except in a few shops or restaurants that still serve and display Myanmar Bier. Burma’s most popular beer, already known to be a product of the economy of the same military that outlawed Aung San Suu Kyi’s party in a coup two years ago, is now the symbol of the silent resilience of millions of Burmese people. The boycott campaign, which began shortly after the coup in 2021 and is now two years old, is a reality we have touched upon in all the restaurants, cafes, street vendors, shops and shops. Here, the products of all those companies more or less directly linked to the military – the real masters of the local economy – are completely boycotted. It is a telltale sign that the war being waged, the one that crosses the entire country with the exclusion of the capital or the centres along the Irrawaddy river, is fought silently but sternly, even where no shots are fired. Take Yangon, for example. There, the apparent calm is punctuated by daily attacks. “The resistance doesn’t have the strength to take the city, but every day it makes itself heard,” confides a European diplomat. “You don’t see any military around? Of course, they are targets. They only go out in groups otherwise they risk it. They are afraid.”

Our journey in the country begins in Yangon, taking advantage of the window that a few months ago reopened to tourism a country that had sunk into the autarchic Middle Ages of dictatorship: inflation, curfews, electricity when there is any, a ‘black exchange rate’ so official that banknotes are exchanged in the sunlight in shops. The junta needs hard currency and is willing to pay even a third more than the legal exchange rate. Moreover, having a credit card is not of much help: ATMs do not work, banks work hiccups. Myanmar is also a pariah state in terms of banking. That is why the country has reopened land borders with Thailand and air borders for tourists. Few. ‘Until before Covid in Yangon there were at least 90,000 foreigners a day in the peak season,’ confides Kiaw, a local professional. The Covid plus coup mixture was explosive: ‘We are here now but Madrid strongly advised us not to come,’ say two Spanish guys. British, French, Italians do the same: they advise against it. And the embassies do not have ambassadors but only chargés d’affaires, at least for those who do not recognise the coup government.

The risk is real. The Military Council’s (Sac) control over the country is only formal. It operates the highway from Yangon to Naypyidaw and from there one can reach Bagan, the holy city of a thousand pagodas. A kind of unwritten agreement preserves the Buddhist Vatican from assaults. ‘But across the river,’ they say in a bar on the Irrawaddy, ‘you can hear the barrels. In Bagan there is no shooting so as not to offend the Buddha, but just outside it is hell. And not only in the countryside. The junta is preparing for a sham election that the 2008 Constitution requires it to hold after two years that a national security defence action has relieved the incumbent government. So a vote will have to be taken. Theoretically in August. ‘No one will go,’ says Kaung, a hotel manager with no customers, and it is not hard to believe him. Myanmar is a dictatorship where a traveller need not ask questions. They lower their voices a little, knowing that even the walls have ears, but then they get into it: ‘This country is a disaster. Our children,’ says one mother, ‘don’t go to school’. “At the time of the protests,” recalls a father, “ten out of ten teachers went on strike. Then four came back, six had resigned.

The risk is real. The Military Council’s (Sac) control over the country is only formal. It operates the highway from Yangon to Naypyidaw and from there one can reach Bagan, the holy city of a thousand pagodas. A kind of unwritten agreement preserves the Buddhist Vatican from assaults. ‘But across the river,’ they say in a bar on the Irrawaddy, ‘you can hear the barrels. In Bagan there is no shooting so as not to offend the Buddha, but just outside it is hell. And not only in the countryside. The junta is preparing for a sham election that the 2008 Constitution requires it to hold after two years that a national security defence action has relieved the incumbent government. So a vote will have to be taken. Theoretically in August. ‘No one will go,’ says Kaung, a hotel manager with no customers, and it is not hard to believe him. Myanmar is a dictatorship where a traveller need not ask questions. They lower their voices a little, knowing that even the walls have ears, but then they get into it: ‘This country is a disaster. Our children,’ says one mother, ‘don’t go to school’. “At the time of the protests,” recalls a father, “ten out of ten teachers went on strike. Then four came back, six had resigned.

The junta replaces some of the teachers with soldiers, but…’. But ‘rather than send their children to the public school,’ confirms one European official, ‘people hang themselves to send their children to the private facilities that sprang up like mushrooms after the coup’. It is another aspect of the resistance that goes hand in hand with Myanmar beer. But it is much more expensive. Back to the elections. People are smiling: ‘Yesterday they came to the house for the electoral census escorted by soldiers,’ explains the tenant of a building. They are afraid to come alone. The guerrillas of the Defence Forces (POF) have them in their sights. And for collaborators there is no mercy or trial: targeted executions all over the country. Let’s not talk about it in the areas where ethnic militias, the armies of the regional autonomies, control the territory.

“What will happen in the coming months is unclear,” explains a political analyst, “but what is fairly certain is that Aung San Suu Kyi has rejected any kind of mediation with the military that both the junta and part of the NUG (shadow government) would have liked. The effort on which the resistance therefore seems to be oriented is that of a boycott. It is difficult, however, to imagine it unfolding with a strategy that is completely shared by the many forms that the resistance has taken, starting with the many regional armies, each with its own political agenda. ‘What is certain,’ he concludes, ‘is that no signal can be seen from the international community. The Burmese are less interesting than the Ukrainians.

Crossing Myanmar fills the heart with anguish and a sadness that, like an invisible blanket, seems to cover everything and accompany you even inside the airport where – someone warns us – there is always a spy shuttling around to check who is saying what. But despite the apparent victory of the military who, at least in the big centres, have managed to achieve a return to normality forced by the need to bring home an albeit meagre salary, that veil of apparent submission to the inevitable is broken by the subtle optimism of those who think that ‘it will be long but we can make it’. Even while continuing to refuse that bottle of beer which, as they say here, ‘equals two bullets every time you drink it’.

The names of the collected testimonies are fictional. Photos are by the author