by Alessandro De Pascale

Looking down from the hills, the vast agricultural greenhouses of the Piana del Sele (river Sele plain) stretch as far as the eye can see., all the way to the sea. The roads of the Piana, especially in the early morning and at dusk, are full of migrants riding their bicycles. “According to our estimates about 12,000 migrants work in the agro-industrial sector in the plain,” says Anselmo Botte, a trade unionist from the CGIL union in Salerno who has been following the phenomenon for decades. Without these 24,000 workers from Maghreb, sub-Saharan Africa or Bengala, India and Pakistan, the agricultural and buffalo sectors would soon be in crisis.

The ‘Piana del Sele’ is one of the largest, most fertile and most mechanised agricultural areas in the Campania region: 3,600 hectares, of which almost 90% is actually used. From here, fruit, vegetables and the typical Campanian buffalo mozzarella cheese are supplied to the local market and to large-scale organised distribution, even to foreign markets. Large companies with more than 100 hectares of land (the legacy of the old latifundia) and well-known brands in the sector (including foreign ones) invoice millions of euros here.

The problems are obviously many, starting with widespread illegality: drug trafficking, prostitution and human trafficking have long plagued this coastal strip that stretches from Salerno to the Parco del Cilento. Then there is undeclared work. “According to the CGIL’s Red Book, based on data from INPS (the Italian social security agency), 60% of the population does not have a contract, and the agricultural sector is one of the most exposed,” continues Botte. “If 4-5 years ago they earned 20 euros a day on the black market, today those who have been regularised earn twice as much. But even for those who have a contract”, stresses the union leader from Salerno, “there is a discrepancy in the number of days officially worked, which is almost never the same as the number of days actually worked. On average you work almost the whole month, that is 22/25 days, but in the pay packet, when things are going well, it is at most 10/12, so practically half”.

The other major problem is housing. “The housing situation is very bad,” continues Botte. “After the eviction of the ‘ghetto’ of San Nicola Varco in Eboli, there are no more structures of that size. The migrants have spread all over the Sele plain, in the historic centres or along the coast, where they occupy buildings built illegally in the 1970s and 1980s, designed for local tourism and then rented out to migrants”. And not always with a regular lease.

OrtoMondo’s experience fits into this scenario. We are in the municipality of Capaccio-Paestum (22,000 inhabitants), known for its archaeological area with three ancient Greek temples still in excellent condition. The local NGO Legambiente Club, has launched an initiative to bring migrants together in shared housing. They call it ‘human ecology’. Thanks to its long experience in this field, Capaccio-Paestum, together with the Italian cities of Rovigo and Scicli, the French cities of Veynes and Pays de Saint-Aulaye and two districts of Berlin (Germany), has become one of the seven pilot sites of the European project Involve (INtegration of migrants as VOLunteers for the safeguard of Vulnerable Environments), which involves various associations in “voluntary pathways to build and experiment a new idea of European citizenship for more inclusive, safer and cohesive communities”. But the president of the local Legambiente club, Pasquale Longo, is quick to clarify to Atlas of Wars: “We have no funding, everything is self-supporting and we are self-sufficient, giving equal dignity to people who develop their own path”.

The structure in question is a housing complex with one hectare of land and a makeshift football pitch around it. When we visit, it is mid-afternoon, and the residents are returning by bicycle or moped from their agricultural work in the plain. Depending on the season, in the little free time they have, they grow peppers, escarole, lettuce, onions, wheat, artichokes and aubergines at OrtoMondo. They also grow produce from their own land, such as okra, karccade and African pumpkins. They also keep bees for honey.

The building consists of eight independent lodgings (four on the ground floor and the same number upstairs), which can accommodate 16 people. “This is a private building,” says Longo of Legambiente, “previously it was used as an Extraordinary Reception Centre (Cas): 70 guests, compared to our current 14.” When the facility closed in September 2020, the association rented the building: “We pay 1,200 euros in rent, plus utilities such as electricity and gas (on average around 600 euros per month). These costs will soon be reduced as a company in the sector has donated solar panels for our balcony.” All the people who live there contribute to the costs: “Each migrant pays 75 euros a month for their housing,” Longo explains. “The modules are for two people: so living here costs them 150 euros a month, half or even a third of the market price. And of course we support them if they need it”.

The fixtures, furniture and appliances in the OrtoMondo homes are second-hand and come from the collection of bulky items. The Legambiente Capaccio-Paestum project is an experiment, “a model of widespread hospitality that companies should do,” Longo suggests, “through a solidarity pact and perhaps by joining together to offer their employees a home at a reduced price. Ten such structures would give dignity to more than 100 people. Also because it is difficult to provide them with regular housing”.

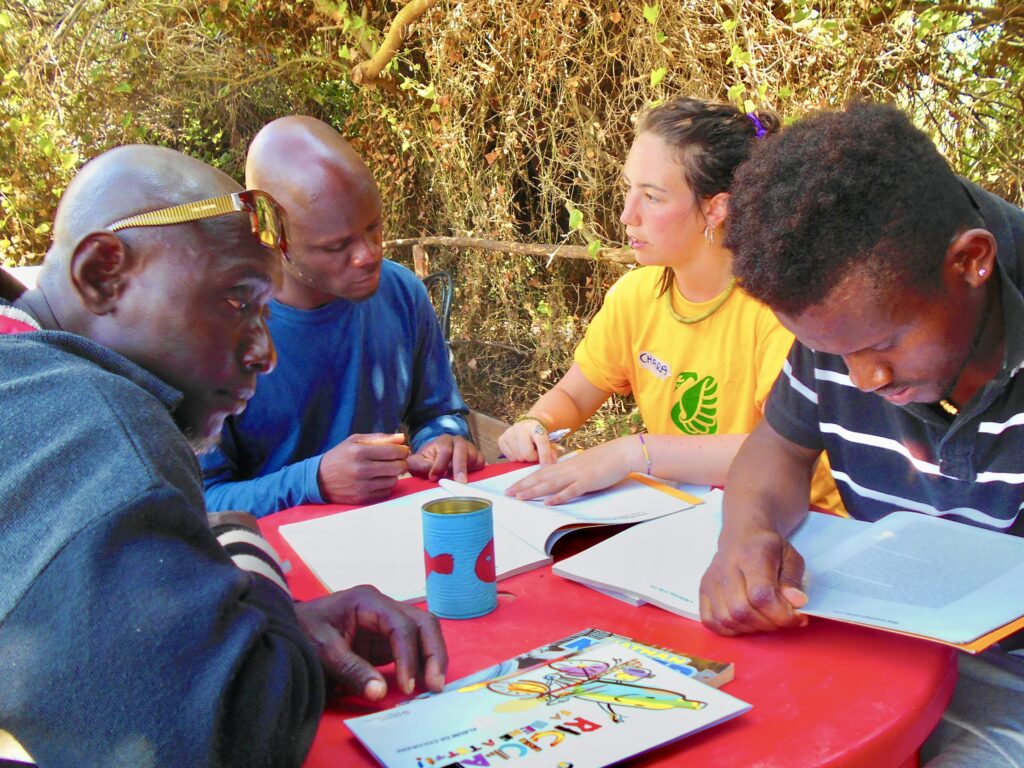

In addition to the communal kitchen garden, Legambiente has set up two bike repair rooms, organised literacy and road safety courses, provided legal support and involved them in voluntary activities. Some of these activities include mowing the grass in the archaeological area of Paestum and cleaning the walls of the ancient Greek city. So much so that some of the most active have, over time, become members of the environmental association. The residents of OrtoMondo are all men in their early thirties with very similar backgrounds. “I define them as third-level immigrants,” continues the club’s president, “because they are legal, work under contract, earn 750-900 euros a month and send money home to their families”.

Kandra, a Senegalese, works in the agricultural sector like almost everyone else: “In the Piana, where I arrived five years ago, I work mainly with sage and lettuce. I have been living in OrtoMondo for 12 months and I get on well there because we have a house, we live together and we support each other. On Sundays, when I finish work early, I look after the communal kitchen garden”.

Malang, also from Senegal, who has been in the Piana for three years, is the most recent arrival at OrtoMondo: “I’ve been here for 20 days, I don’t even have a place to live yet,” he explains, as he moves some poles from a field into the structure that needs to be ploughed.

Then there is Ariu, another Senegalese, who could finally visit his family for 24 days a few months ago: “I took a plane from Naples and was home in six hours,” he tells Atlas of Wars with a smile on his face. “I have a wife and a son in Senegal: when I left he was a few months old, now he is seven”. With OrtoMondo since February 2021, Ariu also works in the agricultural sector of the Piana: “Sage, rosemary, mint and thyme”.

In Senegal, he also worked the land: “I grew maize and melons, but I couldn’t feed my family. Six years ago, I arrived in Libya, crossing Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. A journey that took six months. After 15 days in Libya, I reached Lampedusa by sea and was taken directly to Capaccio-Paestum. The ship was carrying 415 people, five of whom died during the voyage. Luckily we were eventually rescued at sea”. From his new home in OrtoMondo, at the foot of the hill, Aru can see the Piana where he works. But above all, in the distance, he can see the sea, which, like the others, he crossed in search of a better future, risking his life.

On the cover photo: OrtoMondo’s migrant cohousing structure © Legambiente Capaccio-Paestum