A photo essay by Fabio Bucciarelli* for the Atlas of Wars

From Tulkarem and East Jerusalem

Sarah filmed it all with her mobile phone. Standing at the window of her house, her hands shaking, she clutches the device that captured the death of her brother Taha, just 15 years old, killed by three bullets fired by Israeli soldiers: one in the leg, one in the stomach and one under the eye. Sarah’s desperate cries call out to her brother. No one answers. Her father Ibrahim enters the room, looks out the window and asks, “Who is the wounded boy?” Without waiting for an answer, “Is it Taha?” before rushing down the stairs, out of the house and trying to revive him. The pain leaves no room for the thought that the next bullets will be for him. Ibrahim was shot in the back as he embraced his son and died in hospital after four months of suffering.

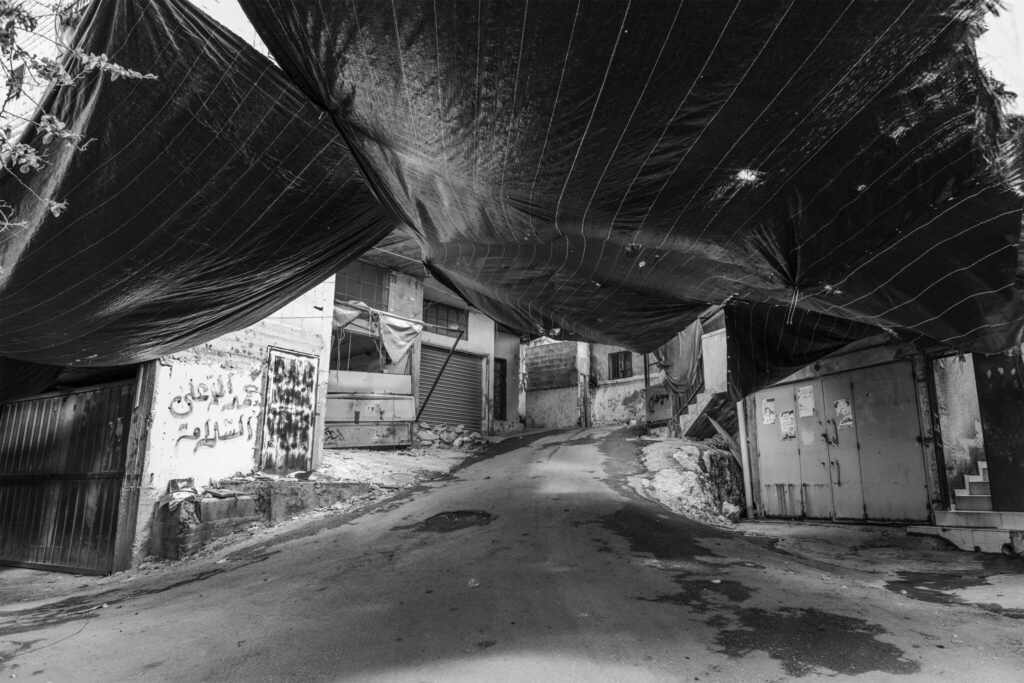

Stories like this are common in the Nur Shams refugee camp in Tulkarem. Raids, explosions and arrests are increasingly common, while the central square looks like a battlefield, with tyres piled up ready to be set alight and collapsed buildings reduced to rubble. With tents piled along dirt roads, communal toilets and associations distributing basic necessities, Nur Shams, like the other camps in the West Bank, does not reflect the stereotypical image of a refugee camp. In 1948, following the creation of the state of Israel and the subsequent war won against the Arab League, over 750,000 Palestinians were driven from their land. Since then, the Nakba has been commemorated every year. This is how the refugee camps were born. After 75 years, they have become real neighbourhoods, with dilapidated houses clinging to each other at a crossroads of streets connected by steps that get narrower the higher you go. Everything takes place in the shadow of large black tarpaulins stretched between one building and another to hide from Israeli drones.

At the end of one of these streets, after another flight of steps, a group of fighters stand guard. There are three of them, two of whom have just come of age. The younger one was cleaning his rifle, while the other two stood around him, learning, leaning against a small concrete wall that bore the scars of explosions. When he saw us, he cocked his rifle and came towards us. We both knew it was unloaded, but his suspicious gaze scanned every crevice of my existence, searching in vain for evidence that might betray me, under my shirt and among my camera equipment. It has become increasingly common to see Israeli agents in civilian clothes, camouflaged, walking around the camp. The fighter has hollowed out sockets around his black eyes, his face bearing the weight of experience far beyond his twenty-one years. He would not give me his name or allow me to take photographs, except of the homemade hand grenades stored in a rucksack that used to hold clothes. The close-cropped beard along his chin gives him determination, but his gaze is elsewhere, focused on a world I do not understand. He barely speaks, words seem to slip from his mouth only to obey an imposed duty. His commander comes to see if everything is all right: he does not look at me, does not speak to me; I am just a shadow in his reality, an infidel, an intruder in a foreign territory. I have seen that emptiness in his gaze before, in Aleppo in 2012, as the war festered and violence bred more violence and extremism.

To date, the Israelis have killed over 34,000 Palestinians in the Gaza war, many of them women and children, not counting the missing and those dying from lack of care. While the imminent attack on Rafah pushes the possibility of a lasting peace further away, tensions in the West Bank continue to rise. Today, the two-state solution is a shattered utopia in the face of the presence of hundreds of thousands of Israeli settlers in territory that does not belong to them. What fate awaits the next generations, raised in a climate of hatred and violence that has now become endemic? What will be the future of those who grow up in an occupied territory, who may have lost a brother, a family member, or a friend? What will be your future if, at the age of 15, you find yourself praying at the grave of a murdered friend, dreaming of becoming a militiaman and, if luck is on your side, a martyr?

Silwan is a neighbourhood in East Jerusalem, one of the places hardest hit by Israel’s colonial expansion policy. Jmailat Al Raibi’s family have lived there for generations, and what I learnt from my time with them is that they will never leave their home, or what is left of it, after the metal claws of Israeli cranes have torn out its walls. “They offered us millions for the land, but we refused. Then, in the middle of the night, the bulldozers came with the military, woke us up and gave us an hour to gather our things and leave”. They destroyed and we rebuilt. Since then, they have been in a legal battle, selling everything they had to pay the lawyer and rebuild their lives. As Jmailat speaks, a television in the dining room sits between two grey plastic chairs, hidden by a red curtain. On the Qatari channel Al-Jazeera, Hassan Nasrallah, the religious leader and secretary-general of Hezbollah, is broadcasting his speech, shouting to the cameras the anger and frustration of his people. In the room with Nasrallah and Jmailat, two of his granddaughters learn the history of their people.

Today is the last day of Eid, the festival that follows the holy month of Ramadan, and as soon as the maqluba is lit, the smoke rises and fills the air. It is an ancient ritual of hospitality and sharing, but also an act of resistance. Maqluba is a Levantine dish of rice, vegetables, chicken, chickpeas and spices cooked together in a pot and then turned upside down on the serving tray: it carries the name and affirmation of Palestinian identity in the context of occupation. Sarah and her family are also ready to serve maqluba, despite the first Ramadan without Taha and Ibrahim. “The day after they killed my brother and mortally wounded my father,” Sarah continues, “IDF soldiers desecrated our house and turned it into an outpost of their occupation. They forced us to witness our humiliation, right here, where we are now. She stands up with her sister Fatima and together they show me the photo of their father, his young face wrapped in a white kefir and supported by a black agal, before walking through a door carved into the wall to another wing of the house: “This is where they put the sniper posts, they destroyed the wall: we rebuilt it, but you can still see it. A patch of stucco covers the holes where the sniper rifles were placed.”

Outside her house, on the very spot where Taha was killed by real weapons, dozens of children play at war, brandishing toy guns and wearing Islamic Jihad headscarves, dreaming of heroism and sacrifice. A few hundred metres away, in the camp’s cemetery, Yasan Fahmawe prays in silence at the grave of his son, whose memory and name remain carved in stone, killed along with five other members of his family by an Israeli drone.

Life in the Occupied Territories is coming to an end. It is also time for us to say goodbye and return to Jerusalem. As the sun sets, the roads often change, making the return journey uncertain. When Israeli soldiers block the way, a never-ending queue forms at the checkpoints until dozens of cars find an alternative route: days lost chasing a target that keeps moving. This, too, is part of the strategy of oppression to which the inhabitants of the Occupied Territories are subjected daily: the fragmentation of the logistical network and the breakdown of communication facilitate control and prevent unity.

The next day, Iran launched its first direct attack on Israel with 320 devices, including 170 drones, 30 cruise missiles and 120 ballistic missiles, in response to Israel’s bombing of the Iranian embassy in Damascus. The following week, Israeli forces carried out one of the most violent raids on the Nur Shams refugee camp, killing at least fourteen people. The seeds of conflict have been sown and are spreading rapidly across the region; only an imminent ceasefire in Gaza could avert disaster.

————————————————————————————————————

* Fabio Bucciarelli is an Italian photographer and journalist. His work in conflict zones has been recognised with the most prestigious international awards, including the Robert Capa Gold Medal and ten Pictures of the Year International. He has worked with Atlas of Wars since its inception. He is the Artistic Director of the WARS Award and a Canon Ambassador