by the editorial staff at AtlanteGuerre.

Negotiations between Lebanon and Israel to demarcate the maritime border have resumed. The US-mediated dialogue had started in October 2020 at a UN peacekeeping base in Naqoura, Lebanon, but talks stalled several times. In a visit in early February 2022, US envoy Amos Hochstein urged Lebanese authorities to resolve the maritime border dispute with Israel, saying it was “the last minute” for an agreement that could facilitate hydrocarbon exploration at sea. The dispute between the two is in fact hampering exploration for oil and gas, of which the area is supposedly rich.

Israel and Lebanon still have no diplomatic relations and are technically in a state of war. Each claims that some 860 square kilometres (330 square miles) of the Mediterranean Sea lie within their exclusive economic zones. The states have thus been engaged in a maritime dispute for more than a decade, while the land border is also still disputed. On the blue line, the UN mission UNIFIL insists.

Neither country has yet been able to extract gas from reserves in the disputed areas. Israel wanted to limit negotiations to the area between Line 1 and the line that Lebanon claimed as its maritime border in 2013, while Lebanon claims that the disputed area is between Line 1 and Line 29. Previously, negotiations had stalled due to what Lebanon called Israeli “preconditions” that would have limited negotiations to a disputed area of 860 kilometres. Israel, for its part, rejected Lebanon’s claims to expand the negotiations to an area of 2,290 kilometres.

At this stage, according to observers, there may be elements of optimism about the negotiations. The Israelis see Lebanon’s increasingly dire economic situation (described by the World Bank as one of the “three most serious economic crises” in almost 200 years) as one of the reasons that could push the country to seek agreement. In fact, the country is facing a serious energy crisis with blackouts, very few hours a day of constant energy and electricity throughout the country. Lebanon has had energy problems for years: losses by the state electricity company, Electricite Du Liban, have contributed to the country’s growing debt. Energy crises are among the causes of popular discontent and street protests that have caused serious social and political tensions in the country in recent years.

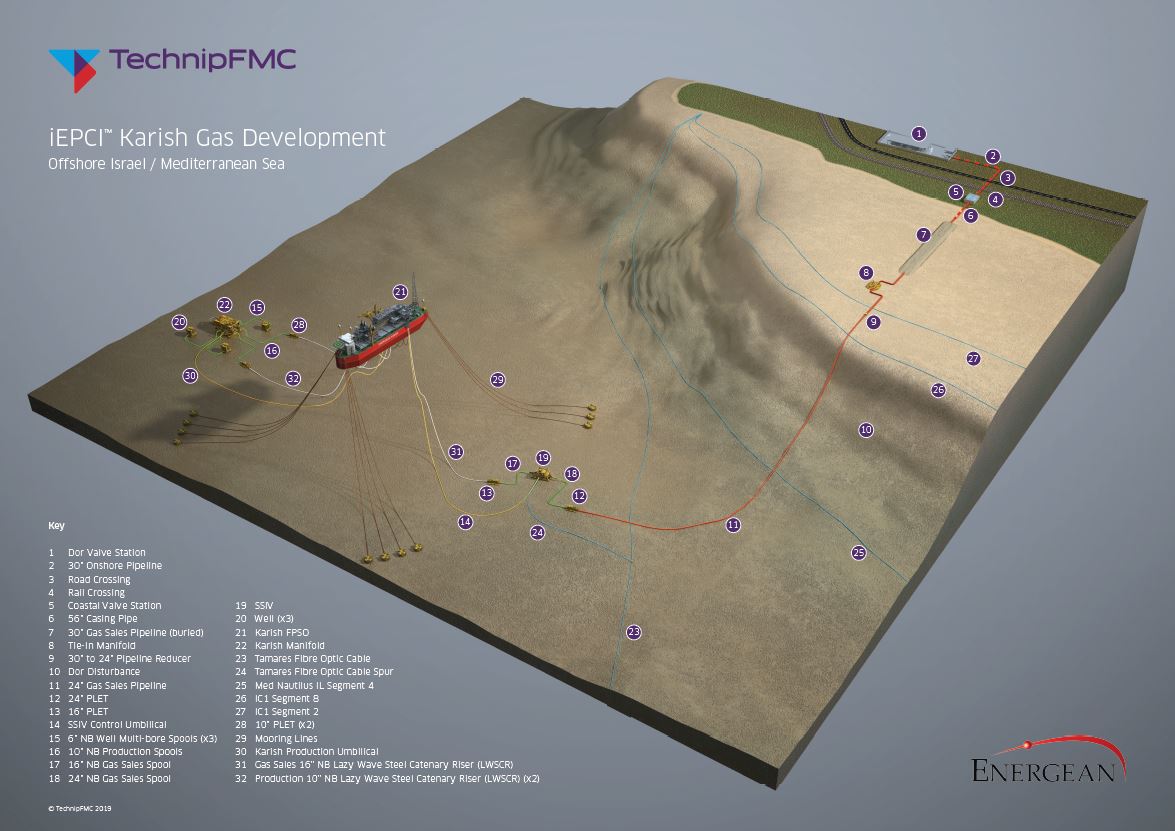

For its part, Lebanon believes that Israel also has a looming deadline. Energean, the Greek energy company that has the rights to exploit the Karish energy field, the natural gas field located off the coast, has taken out a $2.5bn loan to finance the project. The first instalment of that loan, approximately $625m, is to be repaid by the first quarter of 2024. According to Energean, the project is expected to become operational in mid-2022, with first gas production in the second half of 2023. Energean has not said outright that it will not go ahead with production without a fixed maritime boundary, but, according to many, the prospect of carrying out a multi-billion dollar project in disputed waters does not inspire confidence. For the first offshore explorations, Beirut has instead awarded the work to a consortium of Italian company Eni, French company Total and Russian company Novatek in two blocks, one of which is the subject of a dispute with Israel.

Cover image: Alice Pistolesi: the sea over the Blue line, contested land border between the two countries