By Carlotta Zaccarella

As of mid March, the war in Ukraine has caused around 15,000 deaths, 1,900 injured, 3 million migrants forced to leave their homes for safety, 1,700 buildings destroyed and economic damage amounting to almost 119 billion dollars.

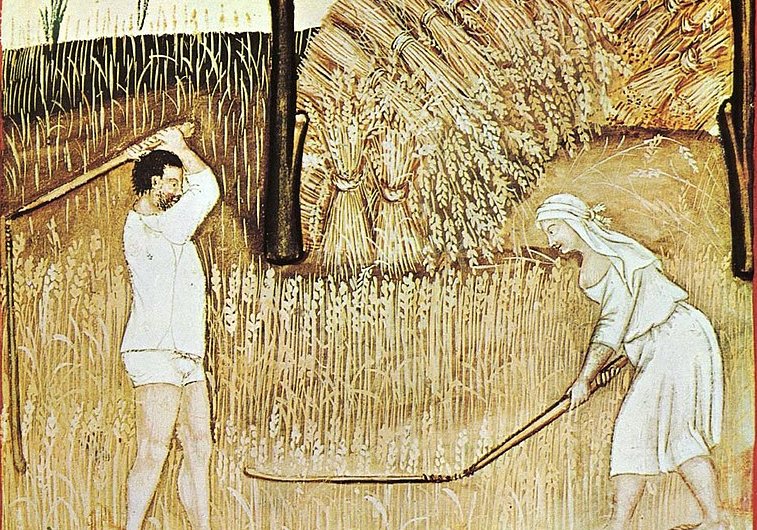

To these consequences, which refer only to the territory in which is being actively fought, must be added the long-range effects of the conflict. In other words, the effects on countries near and far from the battlefield. Among these is the loss of raw materials. Ukraine is the fifth largest exporter of wheat in the world, and the Russian Federation the largest. Together, they produce a third of the wheat that moves around the world for commercial (and humanitarian) reasons.

The situation

For the movement of Russian wheat, the main problem is posed by the sanctions that the international community has imposed on Moscow. For Ukrainian grain, however, the problem is much more serious. First of all, the clashes have hit the southeast of the country hard, where cereal production is concentrated.

Donetsk and Luhansk are Kiev’s breadbasket, but they are also the two separatist provinces whose independence has been recognised by Putin: they are also the centre of the battlefield. In general, then, the countryside has become theatres of confrontation between combatants. Both farmers and their employees have become guerrillas. Agricultural vehicles are sometimes used as military vehicles; there is a lack of fuel to run them. It is difficult to harvest the grain that is now growing in the countryside. Economic analysts dealing with raw materials estimate that up to 10 million tons of grain could be lost in the coming months if Ukrainian farmers are not able to take care of their fields.

These are the tonnes that are expected to enter the international market when the stocks now on the market, which are the July 2021 harvest, are exhausted. The next planting season, crucial for the end of the year and for 2023, is expected to start in April. However, farmers are doubtful about what to do, because they do not know how much longer the conflict will last. They are also short of fertiliser, most of which comes from Russia. In February, Moscow imposed an export ban on ammonium nitrate, the main fertiliser used to grow wheat.

These uncertain factors are compounded by logistical problems.

Transporting the produce is not easy, neither by road nor by sea. Roads, bridges and railways are blocked, damaged or destroyed by bombing, and unsafe. Ports are at a standstill. The Black Sea and its Azov Sea, where the important ports of Odessa and Mariupol are located, have become one of the eyes of the cyclone of war. Cargo freighters are unable to leave and the main shipping companies, including the Italian MSC, have suspended all cargo transport to and from the region: the only exception is emergency materials such as humanitarian aid and medical equipment.

However, the grain remains in the silos of the port infrastructure. There, it risks rotting because problems with the energy supply (mainly electricity) compromise the functioning of the ventilation and temperature control systems and, therefore, the possibility of proper storage of the goods. To get an idea of the damage that the interruption to maritime transport entails, consider that in 2020 95% of Ukrainian wheat left the country sailing the Black Sea.

The second part of this analysis will be published on 21/03/2022.