Restrictive trade policies, more or less extreme weather events, the Black Sea grain export agreement and other geopolitical influences are some of the variables to consider when assessing global price trends. Internal food price inflation remains high in many low, middle and high-income countries. The report on the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023 highlights the state of hunger and food insecurity, as well as the challenges and opportunities posed by urbanisation in the context of agri-food systems.

This dossier provides a brief overview of some aspects related to inflation through the World Bank’s monthly monitoring and the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report.

* Cover photo is by Fotokostic/Shutterstock

Inflation and the Agreement on Wheat

Inflation and the wheat agreement

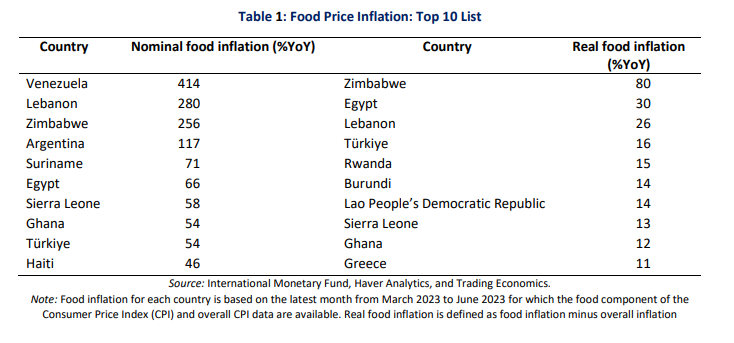

Food price inflation remains high. Between February 2023 and May 2023, inflation is high in many middle-income countries, above 5% in 63.2% of low-income countries and 9.5% in 79.5% of lower-middle-income countries. Many high-income countries are also experiencing double-digit inflation. The worst affected countries are in Africa, North America, Latin America, South Asia, Europe and Central Asia. In real terms, food price inflation has exceeded overall inflation in 80% of the 166 countries for which data are available. The countries with the highest inflation in July 2023 are listed in the table above.

Another issue that has affected food price trends is the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI), which was suspended after Russia withdrew in July 2023. The International Food Policy Research Institute raised concerns about future grain trade due to regional dynamics and Russia’s warnings about maritime security in the northwestern Black Sea. However, despite Russia’s withdrawal, prices have not spiked for the time being. Markets had anticipated Russia’s move due to ongoing geopolitical tensions and grain markets reacted minimally. Prices for major cereals and oilseeds have risen only slightly and wheat prices remain well below last year’s highs. However, if the agreement is not resumed soon, market reactions are expected to be more substantial.

The July 2023 Information System Market Monitor also showed improved prospects for wheat production in the coming season in several countries, including Canada, Kazakhstan and Turkey. Production forecasts for maize in 2023 remained almost unchanged, as did those for rice and maize.

India’s rice ban and the impact of El Niño

On 19 July 2023, India changed its policy on the export of non-basmati white rice to ensure availability and limit price increases in the domestic market. India is the world’s largest exporter of rice, accounting for nearly 40% of the global market, and this halt could lead to significant increases in global prices.

According to the World Bank, the export ban “comes at a time of heightened global concern about international food prices following Russia’s withdrawal from the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI)”. Indeed, the move has raised concerns about the potential escalation of global food inflation. The retail price of rice in India has increased by 11.5% between June 2022 and June 2023, with a further increase of 3% in July 2023.

Rice prices have increased by 20% between February 2022 and June 2023, while wheat and maize prices have fallen by 8% and 4% respectively over the same period. According to the World Bank, some political reactions to the Indian government’s move could destabilise the global market. In 2008, for example, rice prices spiked by almost 250% in the first quarter of the year due to government announcements on exports and imports.

Another factor driving up international prices is ‘El Niño’, which refers to fluctuations in sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean and extreme weather conditions in other rice-producing countries. Climate change can reduce rice stocks, and the potential reduction in supply could exacerbate the price inflation caused by the export ban. Past El Niño events have been associated with yield reductions of between 4% and 11%. A 2023 study also found that the phenomenon reduces global rice production by 1.3%, with an impact of nearly 15% in some areas. Rice-producing countries such as Bangladesh, India, Indonesia and Vietnam are among the hardest hit.

WHO DOES WHAT

Hunger and malnutrition: Data from the Sofi Report

In 2022, an average of 735 million people faced hunger, 122 million more than in 2019. This is according to the latest State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (Sofi) report, published in July 2023 by five UN agencies: the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

While global hunger figures remained stable between 2021 and 2022, many places around the world are experiencing increasingly severe food crises. While progress has been made in reducing hunger in Asia and Latin America, in 2022 an increase was reported in West Asia, the Caribbean and all subregions of Africa. Africa remains the most affected continent, with one in five people suffering from hunger. In 2022, some 29.6% of the world’s population, or 2.4 billion people, lacked consistent access to food. Of these, some 900 million people will be severely food insecure.

Meanwhile, people’s ability to access healthy food has worsened globally, with more than 3.1 billion people (42%) unable to afford a nutritious diet in 2021. This represents a total increase of 134 million people compared to 2021. Millions of children under five continue to suffer from malnutrition: in 2022, 148 million children under five (22.3%) were stunted, 45 million (6.8%) were wasted, and 37 million (5.6%) were overweight.

FOCUS 1

Increasingly Restrictive Trade Policies

Trade policy is one of the main sources of risk to global food price stability. According to the World Bank’s monitoring, trade measures on food and fertiliser have increased since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine. In addition, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, more countries have started to use trade policy instruments in response to domestic needs in the face of potential food shortages. As of 5 June, twenty countries (Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, China, India, Kosovo, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, Russia, Tunisia, Turkey and Uganda) have imposed 27 food export bans and ten countries have imposed 14 export restrictions.

Foods affected by these restrictions include wheat and all its derivatives, sugar, oil, semolina, soya and derivatives, onions, rice, millet, maize, rye, barley, oats, rapeseed, sunflower seeds, beet pulp, vegetable oil, chicken meat, processed fruit and vegetables, tomatoes, potatoes, sunflower oil, eggs, beef, sheep and goat meat. In addition, China, Russia, Ukraine and Vietnam have imposed export bans on fertilisers.

FOCUS 2

Urbanisation and Hunger

By 2050, nearly seven out of ten people will live in cities. The Sofi report shows that food purchases are important not only for urban households, but also across the rural-urban continuum, including for those living outside urban centres. New evidence also shows that consumption of highly processed foods is increasing in peri-urban and rural areas of some countries.

Food insecurity is also increasingly affecting people living in rural areas. Moderate or severe food insecurity affects 33% of adults living in rural areas and 26% in urban areas. Child malnutrition has urban and rural specificities: the prevalence of stunted growth in children is higher in rural areas (35.8%) than in urban areas (22.4%). Food wastage is higher in rural areas (10.5%) than in urban areas (7.7%), while overweight is slightly higher in urban areas (5.4%) than in rural areas (3.5%).