By Alice Pistolesi

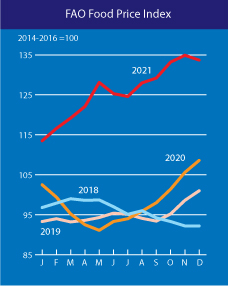

World food prices have increased by 28% in 2021, reaching their highest level in a decade. The Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) food price index, which tracks the most traded food products worldwide, recorded an average of 125.7 points in 2021, the highest since 131.9 in 2011.

This increase affects the entire world population, but obviously has a greater impact on countries affected by conflict and poverty. In this dossier we take a look at the FAO index, analyse some of the causes of the price increase and take stock of who is suffering most from the rise in food prices.

Cover photo by Paz Arando. Graphs by the WFO

Price spikes, according to the FAO index

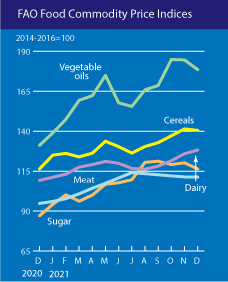

The FAO Food Price Index reached its highest peak in 10 years in 2021. The FFPI, a measure of the monthly change in international prices of a basket of food products, consists of the average of five price indices of commodity groups weighted by average export shares. In 2021, the FFPI averaged 125.7 points, up 28.1% from the previous year with all sub-indices significantly higher than the previous year.

In 2021, the FAO Cereal Price Index averaged 131.2 points, up 28.0 points (27.2%) from 2020 with the highest annual average recorded since 2012. In 2021, maize and wheat prices were 44.1 and 31.3 percent higher than in 2020. This was due to strong demand and tighter supplies, especially among major wheat exporters. Rice was the only major cereal to see a price decline in 2021, with quotations falling on average 4 % below 2020 levels.

For 2021 as a whole, the FAO Vegetable Oil Price Index averaged 164.8 points, up 65.4 points (or 65.8 per cent) from 2020, marking an all-time annual high. Dairy prices averaged 119.0 points, up 17.2 points (16.9%) from 2020. This according to FAO is due to sustained import demand throughout the year, particularly from Asia, and low exportable supplies from the main producing regions.

A price increase was also registered meat, which was up 12.7 percent on 2020 globally. Sheep meat recorded the sharpest price increase, followed by beef and poultry meat, while pork prices fell sharply. Sugar prices also rose. For the year as a whole, the FAO index averaged 109.3 points, up 29.8 points (or 37.5%) from 2020 and the highest since 2016. One cause was concern over reduced production in Brazil due to increased global demand for sugar.

Transport and the "input costs"

According to the FAO’s Food Outlook report, released in November 2021, food trade has shown “remarkable resilience” to disruptions during the pandemic, although rapidly rising prices “pose significant challenges for poorer countries and consumers”. The increase is driven by higher price levels of internationally traded food products and a threefold increase in transport costs.

To examine the impact of rising costs on food input prices, FAO experts have created a new tool called the Global Input Price Index (GIPi). According to the report, the new GIPi establishes that higher input costs translate into higher food prices, but that sectors and regions are affected differently. Soybean producers, for example, have lower demand for expensive nitrogen fertilisers, so they should benefit from higher commodity prices. On the other hand, pig farmers face high feed costs and low meat prices, reducing their margins.

The analysis also indicates a growing number of countries (53 states) where households spend more than 60% of their income on basic necessities such as food, fuel, water and shelter.

Who does what: those who suffer the most

The impact of rising food prices has been greatest in places like Syria, East Africa and Myanmar. The latest report by Italian NGO World Vision investigates how rising food prices are a key factor in increasing levels of hunger and malnutrition globally. The Price Shocks report compared the cost of a basket of 10 basic items in 31 countries and found that while Americans would have to work an average of one hour to pay for the 10 items, people in Syria would need three days and in South Sudan eight days. For example, the cost of bananas now accounts for 58% of the average daily wage in South Sudan and 61% in Chad, countries where hundreds of thousands of people go hungry and risk starvation.

In December 2021, FAO and WFP alerted that the number of people experiencing severe food insecurity had reached a record 28 million in West and Central Africa, the highest since 2014, with levels of acute malnutrition exceeding the 15% emergency threshold in parts of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania and Niger. The increase in hunger, according to the two UN agencies, is driven by prolonged conflict, economic disruptions related to the Covid-19 pandemic, limited access to basic social services and soaring food prices, which this month reached a ten-year high. The poor 2021 rainy season has also affected crop and pasture production in some areas.

The Middle East is also experiencing unprecedented hardship. Yemen and Syria are among the most food insecure regions in the world, while many people in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine and Jordan live on food subsidies and suffer from water shortages, combined with one of the harshest winters ever registered in the region.

FOCUS 1: More meat and bio-fuels

One reason for the rise in cereal prices is related to increased demand for meat from major food importing nations, which has put upward pressure on prices of feed grains such as maize and soya.

Driving the rise is demand for biofuels, which is increasing rapidly in both Europe and the United States as the global transport economy, recovering from the pandemic shutdown, begins to recover. Low stocks of palm oil, a major source of biodiesel, due to poor weather conditions and Covid-19-related production changes have also contributed to the increase.

FOCUS 2: The climate crisis and the race to food stocking

The climate crisis is also a factor to be highlighted. Brazil, for example, recently reduced its corn harvest projection by almost 10% due to the worst drought in almost a century, which shows no signs of abating.

According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington D.C.-based think tank, in the United States, North and South Dakota experienced higher-than-average temperatures and a lack of rain at the start of the harvest season, while Texas was rocked by a winter storm that affected both food crops and livestock. The US Department of Agriculture estimated in its crop report in July that wheat production would decline by 40 percent in 2021 in the Northern Plains and Pacific Northwest. In order to avert higher prices, the largest wholesaler in the US, Associated Wholesale Grocers, which owns more than 3,000 grocery shops, had bought 15 to 20% more inventory.