By Navid Hanif* for Othernews

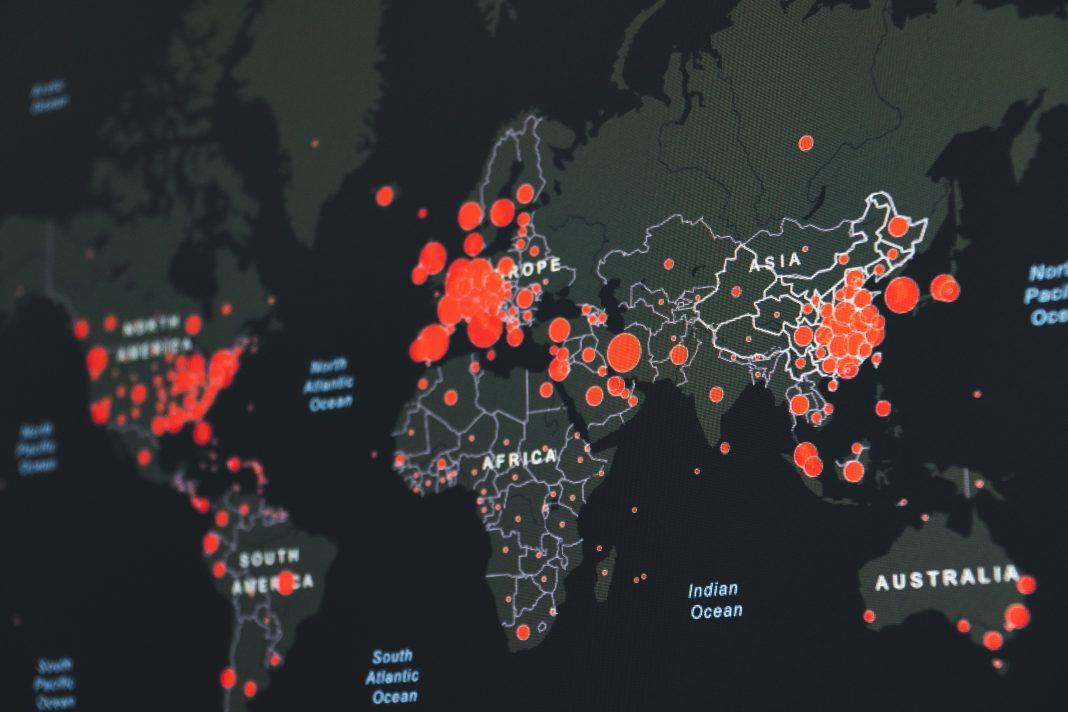

As the world is rocked by a confluence of crises, the global economic outlook for 2022 is becoming ever more uncertain and fragile. Prospects for sustainable development for all and achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030 are bleak, particularly for developing countries. The war in Ukraine is adding further stresses to a world economy still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic and under growing strain from climate change. These cascading crises affect all countries, but the impact is not equal for all.

While some, mostly developed countries, had access to cheap financing to cushion the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic and invest in recovery, many others did not. Massive recovery packages in rich countries contrast sharply with poor countries, which had to juggle essential expenditures. For many, education and development budgets had to be cut to respond to COVID-19.

The UN system’s 2022 Financing for Sustainable Development Report: Bridging the Finance Divide, finds that the ‘finance divide’ between rich and poor countries has become a sustainable development divide. Growth prospects are severely constrained in the developing world – even before taking the war in Ukraine and its repercussions into account, 1 in 5 developing countries are not expected to return to pre-COVID income levels by 2023.

This situation is likely to get worse because the fallout from the war is exacerbating the challenges confronted by developing countries. Food and fuel prices are reaching record highs. This strains the external and fiscal balances of import-dependent countries. Supply chain disruptions add to inflationary pressures, setting up a very challenging environment for Central Banks – rising prices combined with deteriorating growth prospects. Tighter financial conditions and rising global interest rates will make it increasingly difficult, and no doubt impossible for some, to roll over their existing commercial debt.

Many vulnerable countries will not be able to absorb the combined shocks of a disrupted recovery, rising inflation, and sharply rising borrowing costs. Sri Lanka has just defaulted, and more widespread debt distress may well be on the horizon – which is likely to put the Sustainable Development Goals out of reach. The lack of adequate and affordable financing for developing countries is making timely realization of the 2030 Agenda increasingly difficult. Their governments often have few avenues to raise funds domestically, due to underdeveloped domestic financial markets. But borrowing from abroad is both risky and expensive, with some African countries paying over 8% on their Eurobond issuances in 2021.

As the 2022 Financing for Sustainable Development Report notes, the only way to achieve a more equitable recovery is to bridge this finance divide. It will take determined action, on several fronts.

First, developing countries will need additional concessional public financing. Bilateral providers and the international financial institutions have stepped up in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but additional funding was not enough to prevent this divergent recovery. The fallout from the war in Ukraine is widening financing gaps and countries will need additional support. A first key test of international solidarity will be on Official Development Assistance (ODA). Additional support for refugees from the conflict in Ukraine, while important, must not come at the expense of cross-border ODA flows to other countries in need.

Development banks should make available more long-term countercyclical finance at affordable rates, easing financing pressures during crises. Donors should ensure that multilateral development banks see their capital increased and concessional windows replenished generously. One immediate step that development banks and official bilateral creditors could take themselves is to use state-contingent clauses more systematically in their own lending. This would mean automating debt repayment standstills, providing breathing space to countries in crises. Development banks and development finance institutions at all levels could also work to strengthen the ‘development bank system’. National institutions tend to be smaller and fewer in the poorest countries. They would greatly benefit from capacity and financial support. Multilateral and regional development banks can in turn benefit from national banks’ detailed knowledge of local markets.

Second, we must improve the costs and other terms of borrowing faced by developing countries in international financial markets. Excess returns for investors hint at market inefficiencies. We must close gaps in the international financial architecture – the lack of a sovereign debt restructuring mechanism adds uncertainty – and improve transparency by both debtors and creditors.

Transparency and better information for investors can help reduce costs. Short-term credit ratings are also an issue. Rating agencies assess a country’s creditworthiness over a very short horizon, often three years. Meanwhile, many public investments in sustainable development – in infrastructure, education, or innovation – only pay off over a much longer period.

Credit assessments are systematically biased against long-term investments. Thus, they poorly serve those investors that have long investment horizons, such as pension funds. Long-term sovereign ratings that take into account such investments, as well as long-term risks such as climate change, should complement existing assessments. Scenario analysis can help overcome the inherent difficulties of such long-term assessments.

Countries can also exploit growing investor interest in sustainable development and climate action. Sovereign green bonds, which can sometimes be issued at reduced cost (“greenium”), are a fast-growing market segment. A commitment to marine conservation recently helped Belize achieve more favorable terms with private creditors in debt restructuring. Development finance institutions could also help by providing partial guarantees to sovereign borrowers, lowering interest in exchange for commitments to invest in the SDGs and climate action.

Third, many countries will need debt relief to avoid a protracted and costly debt crisis. Once debt has reached unsustainable levels, providing additional credit, even if at concessional rates, will only delay the reckoning. The current mechanisms to deal with countries in debt distress are clearly inadequate. The Common Framework set up by the G20 in the fall of 2020 was a step in the right direction, but its shortcomings have become all too apparent. No restructurings have been completed yet; there is no good answer to treating commercial debt; and many highly indebted developing countries are not eligible to approach the Common Framework at all.

The G20 must step up efforts to implement and deliver on the Common Framework more effectively. But as a more widespread debt crisis becomes a frightening possibility, a more fundamental reform of the sovereign debt architecture must be on the table as well. The United Nations can provide a neutral venue that brings together creditors and debtors on equal footing to advance such discussions.

We at the UN believe that the SDGs can still be met. But without concerted bold action now on all fronts, the road ahead is looking very bumpy. Timely and bold policy choices will get us there.

*= Navid Hanif is Director of the Financing for Sustainable Development Office of the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA). He is also the UN sous Sherpa to the G20 finance and main tracks. He joined UNDESA in 2001. He was Senior Policy Adviser in the Division for Sustainable Development and member of the team for the World Summit on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg in 2002. He served as the Chief of Policy Coordination Branch and later Director in the office for Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) support.

You can read more of his work here:

Cover image:Martin Sanchez.