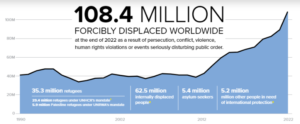

The world is still on the move, and more and more people are being forced to leave their homes. In 2022, the number of individuals forcibly displaced due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations and events causing serious disturbances to public order increased by 21 per cent, reaching approximately 108.4 million by the end of the year. More than one in 74 people worldwide were forcibly displaced, with nearly 90 per cent of them in low- and middle-income countries. In February 2022, the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine triggered one of the fastest and largest displacement crises since World War II. By the end of 2022, 11.6 million Ukrainians remained displaced: 5.9 million within their own country and 5.7 million fled abroad.

The trend continues in 2023: the number of people forced to move is increasing. This dossier highlights some aspects related to the most critical routes in the first months of 2023, both in terms of quantity and violence.

On the cover photo, Migrants on the border between Serbia and Croatia © Ajdin Kamber/Shutterstock.com

Horrors on the border between Yemen and Saudi Arabia

Crisis within the crisis: from Sudan to South Sudan

A project on the Balkan Route

FOCUS 1: The Tunisia-European Union agreement

FOCUS 2: More and more families dream of the USA

Horrors on the border between Yemen and Saudi Arabia

One of the most overlooked borders in the global spotlight is the one between Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Saudi border guards killed at least hundreds of Ethiopian migrants trying to cross the Yemeni-Saudi border between March 2022 and June 2023. This is revealed in a Human Rights Watch report published on 21 August 2023. The report, entitled “They Fired On Us Like Rain: Saudi Arabian Mass Killings of Ethiopian Migrants at the Yemen-Saudi Border,” found that Saudi border guards used explosive weapons to kill many migrants and shot others at close range, including many women and children. In some cases, guards even asked migrants which limbs to shoot. Human Rights Watch based its research on interviews with dozens of Ethiopian migrants and analysis of more than 350 videos and photographs posted on social media and collected from other sources. The NGO wrote to the Saudi and Houthi authorities, who responded on 19 August.

There are currently around 750,000 Ethiopians living and working in Saudi Arabia. Migrants and asylum seekers have told the NGO that they crossed the Gulf of Aden on unseaworthy boats and were then taken by Yemeni traffickers to the Saada governorate, currently under the control of the Houthi armed group, near the Saudi border. Many said that Houthi forces collaborated with traffickers and transferred them to what migrants described as detention centres, where people were abused until they could pay an ‘exit fee’. The migrants regularly attempted to cross the border into Saudi Arabia in groups of up to 200 people, often making several attempts after being turned back by Saudi border guards.

A digital investigation by Human Rights Watch of videos posted on social media or sent directly to Human Rights Watch, verified and geolocated, shows dead and injured migrants on trails, in camps, and in medical facilities. Geospatial analysis revealed the proliferation of burial sites near migrant camps and the expansion of border security infrastructure.

Crisis within a crisis: From Sudan to South Sudan

One of the most significant migration crises of 2023 is that of Sudan and the resulting influx of refugees into South Sudan. Since the outbreak of armed conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in mid-April 2023, forced displacement within the country and into neighbouring states has continued to increase. Sudan hosts over 1 million refugees (the second largest refugee population in Africa), mainly from South Sudan, Eritrea, Syria, Ethiopia, Central African Republic, Chad and Yemen. Over the years, outbreaks of violence have also forced people to flee within Sudan itself. Today, there are more than 3.7 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and more than 800,000 Sudanese refugees seeking safety and protection across the border.

As a result of the conflict, more than 240,000 South Sudanese refugees previously hosted in Sudan have crossed into South Sudan in recent months, in addition to refugees from Sudan. “Refugees and returning South Sudanese – as reported by UNHCR in a statement released on 30 August 2023 – are arriving in increasingly dire conditions in border areas, where access problems, lack of services and deteriorating infrastructure make humanitarian operations extremely challenging. The availability of health care, housing, water and sanitation services for returnees, refugees and host communities is limited.”

But it’s a crisis within a crisis. South Sudan was already facing a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, compounded by the devastating effects of climate change, severe food insecurity and inter-communal violence. “In addition to the urgent need for life-saving assistance,” the UN agency added, “new arrivals will also need support to reintegrate into communities made up of returnees who are themselves fragile and in need of support.”

South Sudan hosts more than 323,000 refugees and asylum seekers, mainly from Sudan, in addition to more than 2.3 million internally displaced people. The ongoing crisis in South Sudan remains one of the largest in Africa due to the large number of people on the move, with 2.2 million South Sudanese refugees having entered neighbouring countries.

Who does what

A project along the Balkan route

Since 2018, Bosnia and Herzegovina has been crossed by migratory flows along the Balkan route.Over the years, the country has set up six transit camps with a total of 5,000 beds. According to various organisations, conditions in these centres are very precarious and do not meet international standards. In addition, there are at least 3,000 people without accommodation, living in improvised shelters in squats, abandoned factories and shelters in the forest. ‘BRAT – Balkan Route: Transit Reception’ is one of the projects addressing the migration phenomenon in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is a three-year initiative proposed by Ipsia in collaboration with Caritas Italiana and the Italian Red Cross. The project, funded by the Italian Agency for Development Cooperation, operates in the three areas of the country most affected by migration flows: the canton of Tuzla, the canton of Sarajevo and the canton of Una Sana, on the border with Croatia. BRAT works on three levels: political and educational, cultural and operational.

FOCUS 1

The Tunisia-European Union Agreement

After weeks of negotiations, the European Union signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the Tunisian government in July 2023. Although currently non-binding, the agreement represents the EU’s political and financial commitment to Tunisia. This commitment includes, in particular, the initiation of a strategic partnership for the management of migration flows from the North African country. As with previous agreements (such as the 2016 deal with Turkey or the memorandum of understanding between Italy and Libya), according to Openpolis. it, ‘the pact is part of a strategy of aid conditionality and the externalisation of European borders’. The agreement is based on five pillars: macroeconomic stability (the EU commits to supporting Tunisia’s economic recovery), economy and trade (specifically in agriculture, the circular economy, the digital transition, air transport and investment), energy transition, people-to-people links (facilitating exchanges) and migration and mobility (combating human trafficking, supporting border protection).

According to various organisations, the real victims of the MoU are sub-Saharan migrants. Tunisia has become one of the main departure points for migrants trying to reach Europe, and in July 2023 it will be the country from which the most people set off for Italy. The UN refugee agency (UNHCR) estimates that in 2022, 31% of arrivals in Italy came from Tunisia, while 51% came from Libya. In 2023, however, Tunisia became the main transit country for migrants heading to Italy.

Migrants in Tunisia are known to live in extremely precarious conditions. In recent months, hundreds of sub-Saharan migrants have been deported to desert areas near the border with Libya, without food or water, or placed in military zones. There have also been documented cases of round-ups, assaults and forced evictions targeting the migrant community.

FOCUS 2

More and more families dream of the United States

In August 2023, a record number of migrant families crossed the border between the United States and Mexico. According to preliminary data obtained by the Washington Post, the US Border Patrol apprehended at least 91,000 migrants crossing the border, surpassing the previous record of 84,486 set in May 2019 during the Trump administration. Erin Heeter, a spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security, said that the Biden administration was trying to slow illegal entry by expanding legal options and also increasing sanctions. The government has increased the number of deportation flights carrying families, and more than 17,000 parents and children have been sent back since May.

According to the US newspaper, family groups have been the Achilles’ heel of US immigration enforcement for more than a decade. Most migrants in this category who are detained by Border Patrol agents are quickly released and allowed to live and work in the United States while their humanitarian applications are pending. US immigration courts typically take several years to reach a decision, and the process rarely ends in deportation.

During the Trump administration, family crossings have decreased. The “Remain in Mexico” programme had sent thousands of asylum seekers back across the border to await US court decisions. President Biden, who had campaigned on a more humane treatment of migrants, ended the Remain in Mexico policy and closed three family detention centres run by US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Biden replaced the pandemic-era policy with new measures that allow tens of thousands more migrants to enter the United States legally each month, but make it harder for those who cross the country illegally to be released after applying for asylum.

The latest data from Customs and Border Protection shows that more than 50,000 migrants were processed at US border crossings in August, where the Biden administration is allowing up to 1,450 migrants a day to make appointments to enter the country legally using a mobile app. Another Biden programme also accepts around 30,000 applicants a month from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela, granting them permission to live and work in the US for two years if they have a financial sponsor and clear background checks. This programme allows beneficiaries to fly to the United States rather than crossing the border.